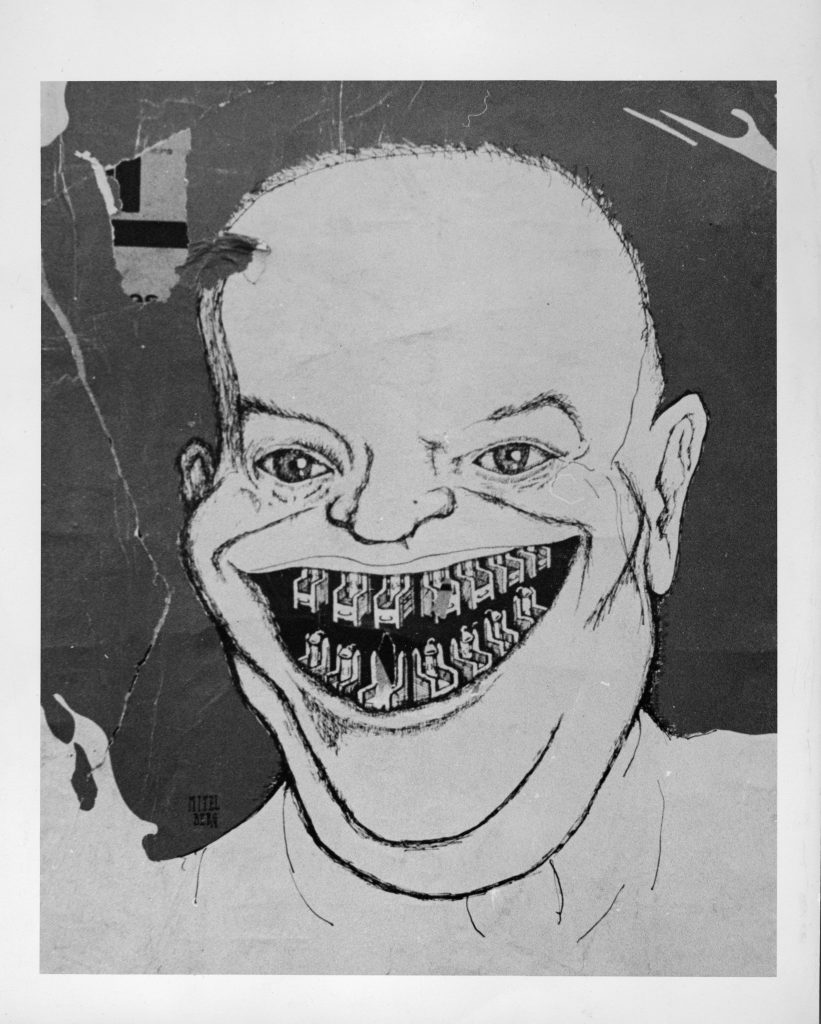

“His Famous Smile” | June 1953

In the months leading up to the June 1953 execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, the streets of Paris were filled with protesters and posters. One such placard that dominated Parisian public spaces was Polish-born French artist Louis Mittelberg’s His Famous Smile. Mittelberg’s pencil drawing depicts President Dwight Eisenhower smiling with electric chairs for teeth. Thousands of Parisians used the image in their rallies, where they protested the imminent electrocution of the Rosenbergs, the only American married couple executed for a federal crime, and the only civilians put to death for conspiracy to commit espionage.

Louis Mittelberg, His Famous Smile, 1952, pencil on paper Wisconsin Historical Society, WHS-3504

Context

In 1950, FBI agents arrested Julius Rosenberg in New York City and charged him with conspiracy under the Espionage Act of 1917. Specifically, officials accused Julius of using his military spy ring to pass “the secret” of the atomic bomb to the Soviet Union. To pressure Julius to confess and name other spies, agents soon arrested his wife, Ethel. After a jury found them both guilty, the judge sentenced the couple to death to further compel them to talk. Julius and Ethel claimed their innocence and refused to name names. The appeals process persisted for two years. President Eisenhower twice denied clemency before Sing Sing Prison officials electrocuted the couple on 19 June 1953, making orphans of their two young sons.

Significance

It is unclear whether Mittelberg was commissioned to create the pencil sketch reproduced in the poster, or if he crafted the unsettling image on his own. Either way it struck a nerve in Paris. As a general during WWII, Parisians had held Eisenhower in high esteem. However, in the early years of the Cold War they became concerned over how President Eisenhower handled the Cold War abroad and anti-Communism at home. Seeing the architect of the D-Day landing depicted smiling through electric chair teeth shocked Parisians and the poster became a powerful symbol for the Rosenberg protest movement.

After the Rosenbergs were convicted and sentenced to death, global protest spread through more than forty-eight countries around the world – from Argentina to Australia, from Iceland to India, and from Switzerland to South Africa. Allies, even those who accepted the couple’s guilt, questioned whether the executions were a necessary punishment. Through 1952 and 1953, the protest movement was fueled by news about the questionable value of the atomic bomb information Julius handed to the Communists, the irregularities and illegalities that plagued the Rosenberg trial, and the minimal role Ethel actually played in the spy ring. Protesters accused U.S. government officials of allowing anti-Communist paranoia to cloud their judgment in sentencing the Rosenbergs. Mittelberg’s drawing, perhaps more than any other single image, motivated the protesters.

The devastating potential of nuclear conflict meant that using propaganda to win hearts and minds was a critical component of U.S. foreign policy. U.S. officials assumed the global Rosenberg protesters were Communist led, but critics – including Pope Pius XII, artist Pablo Picasso, and French President Vincent Auriol – spanned the political spectrum. Protesters, particularly in allied nations like France, decried the gap between American rhetoric and reality that they believed the Rosenberg case highlighted. Louis Mittelberg’s His Famous Smile was an influential image that inspired protesters who believed the handling of the Rosenberg case had tarnished Eisenhower’s, and America’s, global reputation.

Resources

Belmonte, Laura A. Selling the American Way: U.S. Propaganda and the Cold War. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

Clune, Lori. Executing the Rosenbergs: Death and Diplomacy in a Cold War World. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Osgood, Kenneth. Total Cold War: Eisenhower’s Secret Propaganda Battle at Home and Abroad. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2006.

Sibley, Katherine A. S. Red Spies in America: Stolen Secrets and the Dawn of the Cold War. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004.