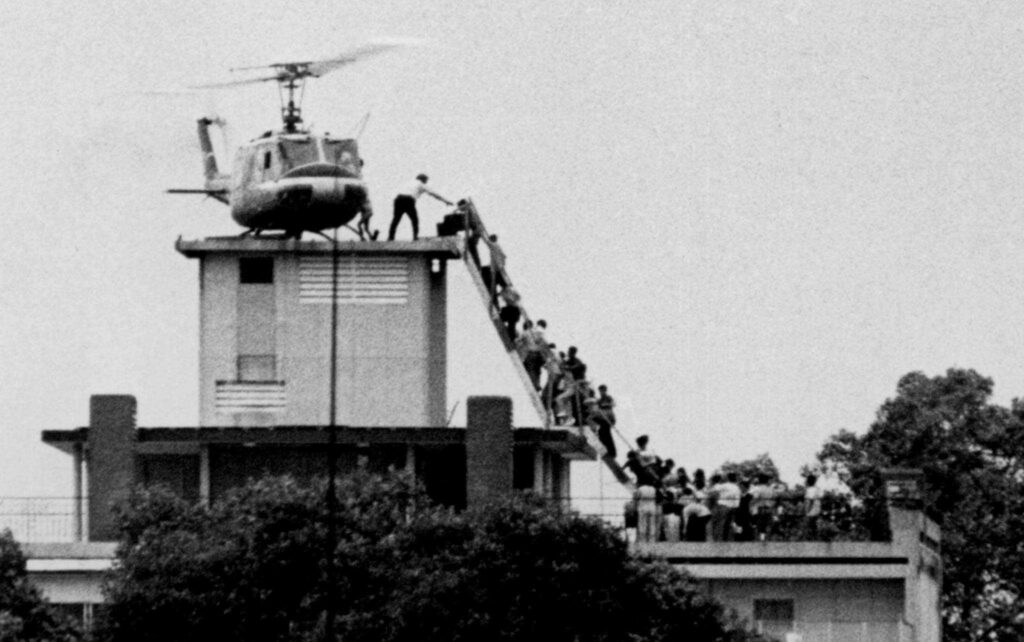

Americans Evacuate Saigon | 29 April 1975

On April 29, 1975, Dutch photographer Hubert Van Es photographed an American helicopter facilitating an evacuation atop an apartment complex at 22 Gia Long Street in Saigon, South Vietnam. Similar scenes played out on rooftops across Saigon that day. In the preceding weeks, North Vietnamese troops captured vast swaths of South Vietnamese territory with stunning efficiency and began closing in on the capital. It became increasingly clear that the Republic of Vietnam (what Americans called South Vietnam) would collapse after a twenty-year existence and that Hanoi would ultimately prevail in the conflict that Americans call the Vietnam War.

Van Es’ snapshot, which was erroneously described in newspapers around the world as depicting the evacuation of the U.S. Embassy about half a mile away, captures one frame in a larger historical moment: the American evacuation of Saigon. The frantic American evacuation demonstrated the extent to which the United States failed to impose its will in Vietnam. In addition to symbolizing the end of the war, the image was widely shown in newspapers and television coverage and has become synonymous with the limits of American power in the twentieth century.

Context

Many features of what Americans call the Vietnam War defy easy explanation, including the war’s conclusion. The 1973 Paris Peace Accords purported to end the conflict, a feat for which negotiators Henry Kissinger and Le Duc Tho won the Nobel Peace Prize. While the Accords facilitated the removal of U.S. combat troops from Vietnamese soil for the first time since 1965 (U.S. advisors had been in-country since the 1950s), the agreement did not bring peace. Rather, the war shifted to a new phase, and in early 1975 the North Vietnamese launched their final offensive. In a matter of months, DRV troops captured (or, depending on one’s perspective, liberated) huge portions of South Vietnamese territory, including the RVN’s second largest city, Da Nang. By the end of April, communist troops were closing in on the capital. In Washington, the Gerald Ford administration worked frantically to respond to South Vietnam’s imminent collapse. After quietly evacuating Americans and South Vietnamese for weeks, Ford implemented Operation Frequent Wind, which called for evacuation by helicopter. It is this final leg of the humiliating American withdrawal from South Vietnam that Van Es captured so vividly in his iconic photograph.

Significance

Van Es’ famous photograph, for which he only received a one-time payment of $150, has become synonymous with the United States’ failure in Vietnam. After spending billions of dollars and deploying over two million Americans, 58,000 of whom did not survive, the United States failed to achieve its objectives. The chaotic final withdrawal dramatized the embarrassment of spending vast sums of blood and treasure only for the U.S. and its allies to lose the war. To add to the sting of military defeat, the war exacerbated fault lines at home and battered Washington’s reputation abroad. Because South Vietnam’s collapse occurred less than a year after Richard Nixon’s resignation amid the Watergate scandal, the humiliating evacuation added an extra exclamation point to Americans’ growing disillusionment with their government. The hasty evacuation and cynical domestic climate also created fertile ground for persistent questions about who might have gotten left behind. Those lobbying on behalf of American servicemen listed as prisoner of war/missing in action (POW/MIA), bolstered by Hollywood films like Rambo, became one of the most powerful domestic political lobbies in the post-1975 United States.

Examining the same image from a Vietnamese perspective provokes an entirely different assessment. The war extracted a catastrophic cost from the Vietnamese: over 3 million perished and another 14 million were wounded as 80 million liters of chemicals and 15.35 million tons of American bombs caused unfathomable physical destruction. For Le Duan, the leader of North Vietnam, the events of late April 1975 were a triumph, the culmination of years of struggle for a unified, independent Vietnam. Although previous offensives had not achieved their intended outcomes, this time the results were unequivocal: on April 30th communist troops crashed through the gates at the presidential palace in Saigon and raised North Vietnam’s colors in a vivid display of victory. The next year, North and South Vietnam were united under a single state, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, governed from Hanoi. If those who fought against the United States were able to watch the American evacuation with a sense of satisfaction, however, they soon learned that peace and reconciliation could be even more difficult to achieve than military victory. The already high challenge of rebuilding after decades of devastating warfare became nearly insurmountable thanks to an American embargo and, more importantly, lack of capital from international financial institutions, which would not invest in or lend to Hanoi without US acquiescence. Any hope for Vietnamese reconciliation, moreover, was quickly dashed by widespread “reeducation” programs and other policies which inspired the exodus of millions from Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, migrations known collectively as the Indochinese diaspora. Finally, war broke out between previous communist allies as Hanoi clashed with Phnom Penh and Beijing in the Third Indochina War, developments which helped spur and exacerbate ongoing financial and reconciliation efforts.

From a South Vietnamese perspective, the same photograph can look starkly different still. The majority of the people in Van Es’ photograph, all of those except the CIA employee standing on the rooftop with an outstretched arm, are South Vietnamese. Throughout the war, South Vietnamese allegiances were complex and the US-RVN alliance was characterized by asymmetries in power, mutual distrust, and significant doses of American paternalism and hubris. Nevertheless, the bonds that were created prior to 1975 did not abruptly disappear with the collapse of the RVN state. In the two decades after 1975, over one million South Vietnamese (and hundreds of thousands of Laotians and Cambodians) resettled in the United States through a series of bilateral and multilateral migration programs. In many ways, then, Van Es’ photograph captures not a decisive end point but the opening snapshot of a new phase in US-Vietnamese relations. Over the next twenty years, as many among the Vietnamese diaspora resettled in the United States, ties between Washington and Hanoi stood at an uneasy state somewhere between war and peace. It took the former foes over twenty years to normalize their economic and diplomatic relations, and the war remains a flashpoint for many Americans and Vietnamese.

Bibliography

Clarke, Thurston. Honorable Exit: How a Few Brave Americans Risked all to Save Our Vietnamese Allies at the End of the War. New York: Doubleday, 2019.

Lipman, Jana K. “‘A Precedent Worth Setting…’ Military Humanitarianism: The U.S. Military and the 1975 Vietnamese Evacuation.” Journal of Military History 79, no.1 (January 2015): 159-161.

Martini, Edwin A. Invisible Enemies: The American War on Vietnam, 1975-2000.

Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2007.

Nguyen, Lien-Hang T. Hanoi’s War: An International History of the War for Peace in Vietnam. Durham, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Nguyen, Viet Thanh. The Sympathizer. New York: Grove Press, 2015.